In her essay “Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry” Kim Tallbear writes of her scholarly struggle “to share goals and desires while staying engaged in critical conversation and producing new knowledge and insights.” Working through this question, she cites Gautam Bhan’s notion of “continuous and multiple engagements with communities and sites of research rather than a frame of giving back.” A problem with ethnographic research, she suggests, is the ever-present necessity of the goal to “give back” to research subjects. To address this, the author proposes shifting the research process into a relationship-building process with colleagues (instead of subjects) so that data gathering might instead look more like information sharing. Using Harding, she writes that we must create “hypotheses, research questions, methods, and valued outputs, including historical accounts, sociological analyses, and textual interpretations” which “begin from the lives, experiences, and interpretations of marginalized subjects”. For Tallbear, placing ethics and positionality first becomes a methodology for knowledge production.

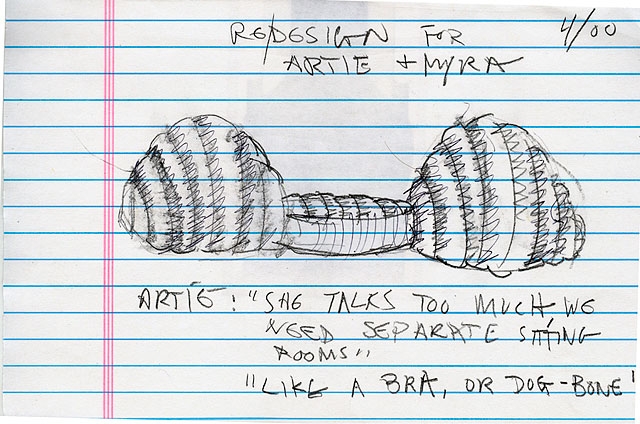

It occurs to me that Michael Rakowitz’ project paraSITES might function well within the terms of Tallbear’s ethical methodologies while also raising some questions for me about the process through which I hope to approach my ‘extratextual’ project. In the late 90s, Rakowitz began constructing lightweight, inflatable living spaces for homeless people. These paraSITES fed on warm air from exterior ventilation ducts on buildings to function as heated habitats for the homeless.

The artist worked with homeless people when creating custom dwelling spaces based on the needs and wants of folks in his local community. He spoke with the homeless, allowing them to craft their own living spaces; letting the project develop from the experience of the subject. Rakowitz aims to provide shelter for his ‘subjects’ by producing custom, warm, cheap, and lightweight sleeping sites.

Although I think the work is important, I wonder about some of the ethical issues that Tallbear brings up. An important part of Tallbear’s methodology is eliminating insider/outsider binaries. But how can an artist or scholar, like Rakowitz or myself, ever begin to legitimately claim insider status within a homeless community. Tallbear’s essay is inspiring on many levels for the ways in which it calls for a more (inter)active researching role and seeks to reposition relations between subject and object. However, I am still left unsure about the ethics of my varying projects in relation to ethnographic studies of homelessness. It seems that mixing Bhan’s call for “continuous and multiple engagements” with subject communities and Tallbear’s proposal to “begin from the lives, experiences, and interpretations of marginalized subjects” might function together as a more accessible method as I approach homelessness in my work.